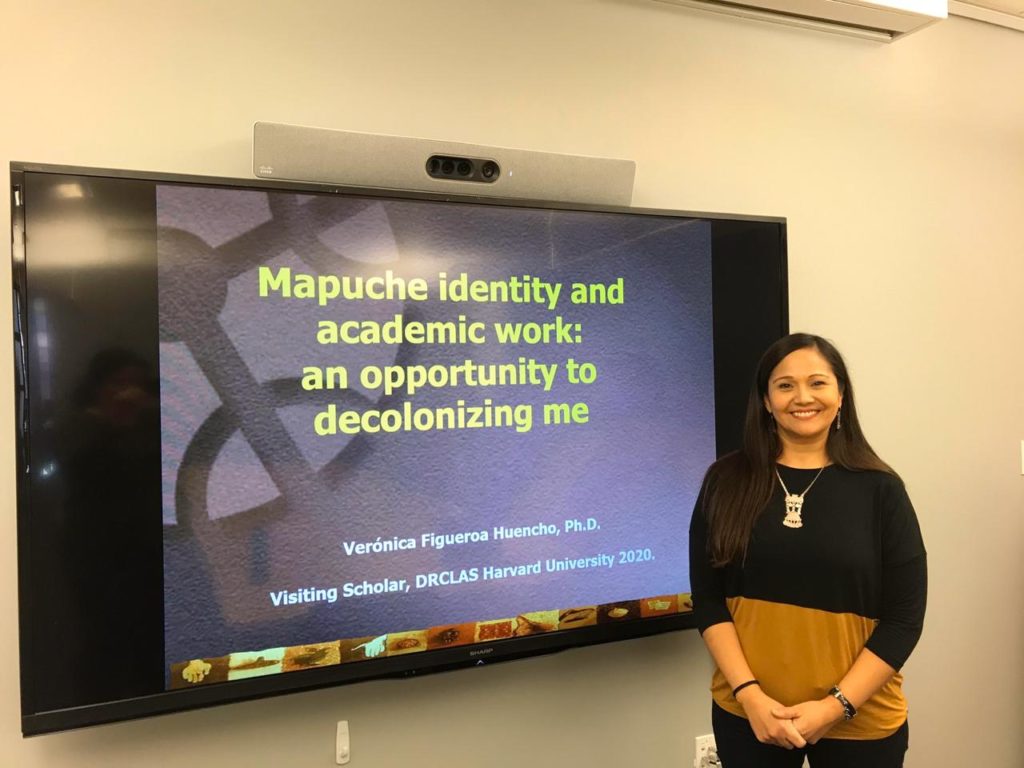

Verónica Figueroa Huencho, our current beneficiary of the Luksic Visiting Scholars program at Harvard University’s David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, is a public administrator at the University of Chile, Ph.D. in Management Sciences (ESADE-Universidad Ramón Lull), Postdoctoral Officer at Stanford University’s Center for Latin American Studies.

Verónica has extensive experience in the academic field, in gender issues, and above all, in the search for the inclusion of indigenous people in Chile within public spheres and their access to better representation.

Her fundamental field of study elaborates on the formulation and implementation of indigenous public policies within contexts of diversity. She has publications in ISI indexed journals as well as books and chapters of books in both national and international publishing.

We sat down and talked with her to delve more into her main line of research and to understand the context in which we find ourselves in Chile.

What are the main challenges in terms of diversity and representation?

As for the representation of indigenous people, one of the greatest limitations that exists today, in Chile and the rest of Latin America, is that most states have taken on the nation-state model. Therefore, it is understood that when a state governs a territory it is done so in a homogeneous manner. This also has to do with the fact that when the Latin American states were created, the State of Chile in particular, there was this idea of what it would be like to form an ideal nation that was not going to relate to pre-existing nations (given that they were not contributing to development). Indigenous people were considered barbaric, savage beings, and the idea was to create a modern state; a state reflecting European society, therefore, making it a Nation-State -a group of people who share the same language, etc.- the State would being created on the basis of denial… That always, of course, has been a hindrance for indigenous people to be able to move towards more effective systems of representation.

These types of very complex problems are not going to be solved from a single point of view. I suggest we try identifying, within the State of Chile for example, what the main dimensions or variables are that would change the rules of the game, and ultimately, favor the participation of the indigenous. This would lead to the construction of a more inclusive, diverse society; a society in which indigenous people are not seen as folkloric or annexed, but rather as people that enrich the Chilean nation and who have rights. These rights, moreover, have been progressively recognized within the international framework and the State of Chile has ratified these through various covenants and agreements, but its institutional adaptations have not been enough.

The big question for me is what model of governance should be implemented in Chile in order to consider the rights of indigenous people as political subjects and to favor, of course, a better coexistence which – I believe – is what we all hope for.

So, what is the main challenge with representation? It has to do with this logic between Western thought and non-Western thought, and therefore, the way in which the indigenous thinking is represented.

Perhaps the need for a cultural and mental change is also another element. As long as those who make decisions are only validating one way of thinking, it is more likely that their relationship with indigenous people will be established in a hierarchical, subordinate way, viewing them as possessors of alternative knowledge. Therefore, it seems to me that a cultural change, in terms of status, is also needed in order to equalize the value of knowledge that comes from indigenous people.

How do you think the issues related to equality and inclusion in Chile have evolved over the past decade?

“Representation of indigenous rights” is one of the most precarious terms and, compared to other Latin American countries and other countries worldwide such as New Zealand, Canada, and Australia, what we clearly see here is that states have ceded the spaces of rights for a representation of multiculturalism. We, as indigenous people, speak of the need for interculturality because within one territory there coexist different groups and these, of course, have distinct cultures. However, the rules of this hegemonic-culture-game have obviously incentivized the use of a single language and a single way of dressing. This has led the indigenous people to take our culture into the private sphere, mainly into the family realm and, therefore, leaving the public, educational, and decision-making spaces.

The indigenous do not have any specific system of representation in the institutional structure of the State nor in any of its powers. The law, in a rather limited way, refers to the existence of ethnic groups in the territory of Chile, which limits the effective exercise of rights that we have as a nation. It is a different legal concept by a different standard; a different status.

What can you tell us about “cohabiting and multicultural management”?

When speaking of coexistence and multicultural management in the here-and-the-now, we cannot avoid the approach to rights. This has been very powerful in being able to situate the demands of the indigenous people; to have them no longer seen as mere peasants or poor citizens of a territory, but rather, as subjects of differentiated rights and, therefore, with the right to have systems of differentiated representation.

Today, what we do not want happening is the idea that “indigenous” becomes associated with pre-modernity and, therefore, implying that we do not have anything to contribute to development. I believe very powerful ideas have emerged from indigenous knowledge surrounding flora and fauna, the management of territorial spaces, and other environmental contributions. This can become a means of improvement. We cannot allow our own developmental possibilities to be limited because we are incapable of valuing knowledge that comes from other spaces, such as those of the indigenous. We want to contribute, but not from a residual, subsidiary vision, but rather as key actors.

In today’s world and within this context, what makes a good citizen?

The ability to recognize intercultural diversity because there is no one single type of citizen, there is no one common good, rather there exists the same objective which is to create a good coexistence and have multiple ways of obtaining this. It has to do with the representation and participation of indigenous people; it has to do with a good citizen being an intercultural citizen.

According to your vision and experience, is there a lack of support networks and spaces for discussion in Latin America for people of indigenous descent?

Yes, there is [a lack]. What we are suggesting here is that the State’s paternalistic-welfare logic used toward our people has been quite harmful because it has generated an idea of dependency (this is how Chilean citizens and the Western society see us).

It is important to consider that there are indigenous people today who have the ability and the knowledge to participate in forming policies and to better identify public policies with new visions and thus, improving the implementation of these policies.

It is very important to incorporate other actors as well and to understand that we are not asking for assistance; rather, we are asking for our legitimate right to participate and represent our people because we have the ability to do so. This requires communication with other actors, and the business world is fundamental; society itself is fundamental, as well as NGOs, in order to make progress in governance.

As a Mapuche scholar, what do you feel is your greatest contribution toward the debate surrounding the demands of the Mapuche people?

It seems to me that an opportunity like this [to be at Harvard University] has to do with decolonization and how one can contribute from such an elite and powerful space such as the one formed at this university. I think my main role is to provide arguments and information so that indigenous people, in this case the Mapuche people, have better tools to discuss, to argue, and to be represented before the State, before companies, and before different actors of power. It seems to me that this is where I can make an important contribution.